An Article about Perinatal OCD

- Catherine Benfield

- May 21, 2023

- 8 min read

Updated: Feb 13, 2025

*** I should just state at the start of this that even if your OCD does not involve the perinatal period - this should still be helpful for you. OCD is OCD. 😊 ***

Hey everyone!

I recently wrote a piece on Perinatal OCD for the British Journal of Midwifery. Originally a subscription piece, they have kindly made it completely free for everyone to access and read.

Last weeks BBC article was a fantastic awareness piece for the public and I'm so grateful for the opportunity to get my story out to the general population but it doesn't cover everything about the condition.

This does.

It took weeks to research, fact check, write and then edit. Thank you so much to the wonderful ladies at Maternal OCD for their help with the editing process. We knew what a big piece this would be and how important it was to get it right and thankfully we seem to have done it justice.

According to copyright, everyone is now allowed to share this so please, if you can, share it with anyone you think may benefit. I've sent it to my local GP and hospital. I know that someone else is taking it to their GP to help get a diagnosis and someone else using it to help explain to their family that they have the condition. I even heard this morning that a perinatal mental health team has recommended the article and blog to their patients - I was truly blown away by that - so incredible!

Let's get this out there!

And if you ever get the chance, please say a huge thanks to the BJM for making this free - it's brilliant to have them on our side. 😊

Here it is...

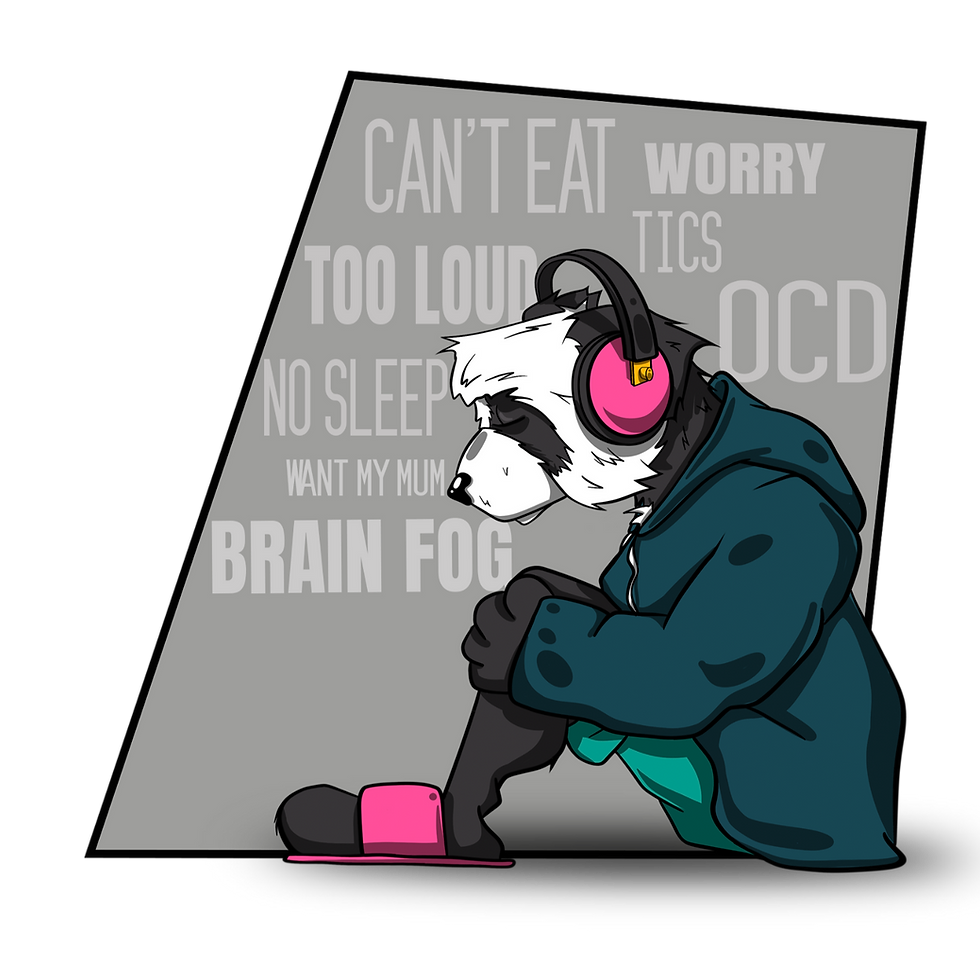

Abstract Obsessive compulsive disorder can have devastating effects on new parents, but is under-researched and poorly understood. Catherine Benfield explains the condition and what midwives can do to help

Introduction

If you had told me 5 years ago that at some point in the future I would be talking to midwives about the nature of my intrusive thoughts, I would be amazed. Amazed and terrified. That's because 5 years ago I was unknowingly experiencing perinatal obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). I was having the most intensely graphic, unwanted, recurring intrusive thoughts about harming my newborn son and, as lovely as I'm sure you all are, you were the last people I wanted to tell about it. I was worried that if I did, you'd begin the proceedings to have my son taken out of my care. My experience with perinatal obsessive compulsive disorder I've lived alongside undiagnosed OCD since childhood, but I didn't recognise intrusive thoughts, which I started experiencing almost straight after childbirth, as a symptom of the condition until I researched it myself, and had it confirmed in my first cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) session. By this point my son was 2—it had taken me 2 years to get help.

Sadly, along the way, my recovery was impeded by a lack of knowledge about the condition, and the myriad ways in which it can manifest. My progress is thanks in no small part to me, and my refusal to stop pushing for help. None of the medical professionals I met within my first year of motherhood identified my symptoms as OCD. I was assessed for postnatal depression and psychosis, but postnatal OCD was never mentioned. It was only when I crumbled under the weight of my intrusive thoughts and started experiencing suicidal ideations that I saw a GP who recognised anxiety and started the process of getting me adequate support.

‘OCD is an anxiety disorder and is thought to affect 1-2% of the population’

Today, I am well—better than well; I am doing brilliantly. I've been through a 3-year recovery journey that's involved CBT and exposure and response prevention (ERP), both of which are the standard treatment for OCD, and I have taken medication on and off throughout this time. I have learnt a lot about self-care and wellbeing, and the condition itself, and I am back to living a completely normal life.

I don't blame anyone personally for my higgledy-piggledy road to recovery. I realise that these things happened because of a lack of understanding about the way OCD works and that's down to training options and a lack of OCD services, not the individual. I'm honoured to write this today, to help spread awareness, and to help you recognise the condition in expecting and new parents. Between us, we can help stop my story being repeated. What is obsessive compulsive disorder? In order to recognise perinatal OCD, it's important to understand how OCD works. OCD is an anxiety disorder and is thought to affect 1-2% of the population (Torres et al, 2006). It is a condition surrounded by a great deal of misunderstanding and misconception, with the term often being used incorrectly to describe those with a love of order, perfection or cleanliness. Thankfully, because of advancements in awareness and understanding, this is changing.

At its simplest, OCD is a condition characterised by obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions are often referred to as unwanted recurring intrusive thoughts, although they can also be experienced as images, urges, bodily sensations and/or doubts. Obsessions cause a great deal of distress, because they often center around harm coming to loved ones, or the things the individual holds most dear.

To reduce the anxiety brought on by the obsessions, those with OCD carry out compulsions. Compulsions are certain behaviours that the sufferer feels compelled to carry out, which could be a physical action or a mental ritual. The relief of having carried out a compulsion is only felt momentarily, and very soon the individual will find themselves wanting to repeat the behaviour again and again until they get caught in an OCD cycle, a state where the compulsions drive the obsessions and vice versa. It doesn't take long for the symptoms to intensify to the point where daily life is seriously impeded. What is perinatal obsessive compulsive disorder? Studies suggest that perinatal OCD affects 1% of women in pregnancy and 2.9% of women in the postnatal period (Fairbrother et al, 2016). Interestingly, and just as a comparison, this study also found that anxiety disorders were more common than depression in mothers during this time, something that is not reflected in the level of awareness and identification for both conditions (Matthey et al, 2003). Sadly, there is very little research available on fathers and OCD.

There are a range of potential risk factors for perinatal OCD. New parents may find that their previously existing symptoms intensify in the perinatal period, with their obsessions shifting to focus on their children, or they may experience OCD for the first time after becoming a parent. It has been suggested that a heightened sense of responsibility and an increase in harm-centred thoughts during the perinatal period could lead to an onset of perinatal OCD (Fairbrother and Abramowitz, 2007).

Just as in non-perinatal OCD, individuals feel driven to carry out compulsions as a way of stopping the perceived harm happening. Compulsions could range from staying up all night to check on their child's breathing, to excessively cleaning to stop the spread of infection. Parents may spend hours scanning for information on the internet or undertaking mental rituals such as reviewing or replaying events in the past, praying, or mentally repeating sentences and words. A particularly frightening, yet common, side effect of perinatal OCD is one that involves parents worrying that they themselves pose a risk to their child. They may experience intrusive thoughts or urges about deliberately harming or abusing their child. It is essential to understand that study after study shows that intrusive thoughts about infants are common in new mothers and fathers (Abramowitz et al, 2003) and that that intrusive thoughts of all types, including deliberate and accidental harm, are experienced by mothers who do not have OCD (Fairbrother and Woody, 2008). The difference between those with OCD and those without is the way the thoughts are interpreted, not that they happened in the first place (Abramowitz et al, 2006).

Due to this perceived level of threat, parents may carry out compulsions as a way as a way of securing the child's safety. They may leave the family home, or refuse to be left alone with their children. Parents may remove knives from the house, double lock all windows, or sit on their hands. Those with OCD may question others repeatedly about the nature of their own thoughts and experiences as a way of checking their perceived level of risk. They may also undertake mental rumination, which is much, much harder to identify.

An understanding of perinatal OCD in midwives is essential, as the condition can have a huge effect on new parents and their families. Women with OCD report a significant effects on their quality of life, parenting tasks, relationships with partner and perceived social support (Challacombe et al, 2016).

What you can do

This article covers many of the manifestations of OCD in the perinatal period, but it is an ever-changing condition and one that, depending on the nature of the compulsions, can be challenging to recognise and identify. Here are a few things you can do to help:

Ask new parents if they have any concerns, or if they are experiencing any anxiety or upsetting thoughts or urges. Is the parent looking to you for a lot of reassurance?

Keep an eye out for repetitive physical behaviours or signs that parents are withdrawn or distracted—this may indicate internal compulsions and rituals

Parents may show signs of depression and generalised anxiety. Gentle questioning will help decipher if this could be OCD-related

Be aware that perinatal OCD can also be referred to as maternal OCD, paternal OCD, postnatal OCD and postpartum OCD. There is further reading available under each title

Let new parents know that OCD is an anxiety disorder and that there is no shame in experiencing upsetting intrusive thoughts. This is especially the case for those parents experiencing intrusive thoughts about harming their child—OCD is a condition that attacks the things people hold most dear and for most people, that is their child.

Provide hope and let parents know there is help and treatment available, most notably CBT with ERP and/or medication.

Conclusion OCD is a disorder that can be devastating for both the person with OCD and their loved ones. It is a condition surrounded by misconception and stigma, and research is hugely lacking, but thankfully changes are starting to happen, and awareness is starting to spread. As midwives, you are in a fantastic position to both recognise the condition in new parents and to help get the correct support in place. With your support, new mothers and fathers experiencing OCD can quickly get back to the job they most wanted to do in the first place: being wonderful, healthy, parents to their children. BJM

For more information and guidance, visit the Maternal OCD website.

And there you have it - I hope it helps.

As always, loads of love

Catherine xx

Further Reading

The Taming Olivia Newsletter!

We bring out a monthly newsletter that contains a whole world of information about OCD, Taming Olivia, the OCD community, helpful freebie play sheets to help you practice new skills, and updates about our multi-award-winning film about OCD and intrusive thoughts, Waving. If you fancy joining our wonderful Taming Olivia Community please sign up on the home page.